Variation to the terms of a Marketing Autorisation

Introduction

After a Marketing Authorisation (MA) for a medicinal product has been granted by the relevant authority in the European Union (EU), the regulatory activities are referred to as post approval lifecycle management. Considering all of the activities for a clinical trial and the marketing authorisation application, you would be forgiven for thinking that all the hard work has been done and that it is the end of things as we know it. I think it is not really the end of things, it’s almost like a new beginning. Post approval lifecycle activities are just as interesting and challenging as pre-approval activities from a quality and regulatory perspective.

The regulatory applications submitted for post authorisation are:

renewal applications

periodic update safety reporting

post-approval commitments (such as CMC commitments and other commitments (e.g., post authorisation safety studies) and

applications to vary the terms of a marketing authorisation (including line extensions, rebranding, urgent safety restrictions)

This blog focuses primarily on the applications to vary the terms of a marketing authorisation in the European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA); I will briefly discuss some impacts on licences in other regions.

EU and EEA

A brief description of the distinction between EU and EEA member states seems appropriate.

The EEA countries are not necessarily the same as the EU countries (member states). All EU members are automatically EEA members, but not all EEA members are EU members. The 27 member states of the EU are listed here. The EEA member states are Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway; they are the European Free Trade Association states (EFTA states).

The European Economic Area Agreement entered into force on 1 January 1994, bringing together the EU member states with the EFTA states. Its purpose is to ensure the free movement of goods, services, people, and capital throughout the 30 EEA states; this is achieved by strengthening trade and economic relations, removing trade barriers, and imposing equal conditions for competition and compliance. This agreement covers research and development, the environment, consumer protection as well as other policies not relevant for discussion in this blog. Importantly, the EU regulatory framework is applicable to Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway, and these countries can fully participate in EU regulatory applications which includes variation applications (unlike the UK because of Brexit). Mainly, when I refer to the EU, I also include the EFTA countries.

Marketing Authorisation

A marketing authorisation (MA), lays down the terms under which the marketing of a medicinal product is authorised in the EU and consists of a decision granted by the relevant authority and a technical dossier which was submitted by the applicant, reviewed and approved by the relevant authority.

MAs are granted through the following routes:

National route – the regulatory authority is a National Competent Authority (NCA), a single member state. Directive (EC) No 2001/83/EC

Decentralised (DCP) or Mutual Recognition (MRP) Procedural routes, several member states (one reference member state and one or more concerned member states) Directive (EC) No 2001/83/EC.

Centralised route, the authority is the European Medicines Agency, the ‘Agency’, the decision applies all of the member states of the EU. Regulation (EU) No 726/2004.

Any amendment to a marketing authorisation requires a variation application. Amendments include the information in the technical dossier, any conditions, obligations, or restrictions affecting the MA, or changes to the labelling or the package leaflet connected with changes to the summary of the product characteristics. The examination of an application for a variation to the terms of a MA must comply with the EU Variation Regulation (EC) No 1234/2008.

Overview of variations to the terms of a marketing authorisation for medicinal products for human use.

All variations must be submitted via the route through which the MA was granted unless submitting a variation using the worksharing procedure. Therefore, a variation to a medicinal product granted through the DCP route must be submitted and assessed through this route and not through a national route to one member state in a DCP procedure, even if the variation only concerns the one member state.

Change of ownership applications must be progressed through the national route (at least as far as I am aware, the last time I did one). They are not the same as variations.

The variation regulation does not apply to changes to the labelling or package leaflet that is not connected to the summary of product characteristics – this is an Article 61(3) notification.

Variations are categorised in accordance with the potential risk or impact to quality, safety, and efficacy.

In the EU the following categories of variations apply:

Minor variations of Type IA or Type IAIN - (Type IAIN are immediate notification to be submitted within 2 weeks of implementation date) Type IA submitted within 12 months of implementation.

Minor variations of Type IB - implementation upon approval

Major variations of Type II - implementation upon approval

Extensions - implementation upon approval

Urgent safety restriction - implementation on approval; date agreed between the marketing authorisation holder and the regulatory authority.

Variations submitted by marketing authorisation holders (MAH) can be progressed in different ways; they can submitted as single variations, as a group of variations or part of a worksharing procedure to the relevant regulatory authority.

The below information was obtained from the EMA website:

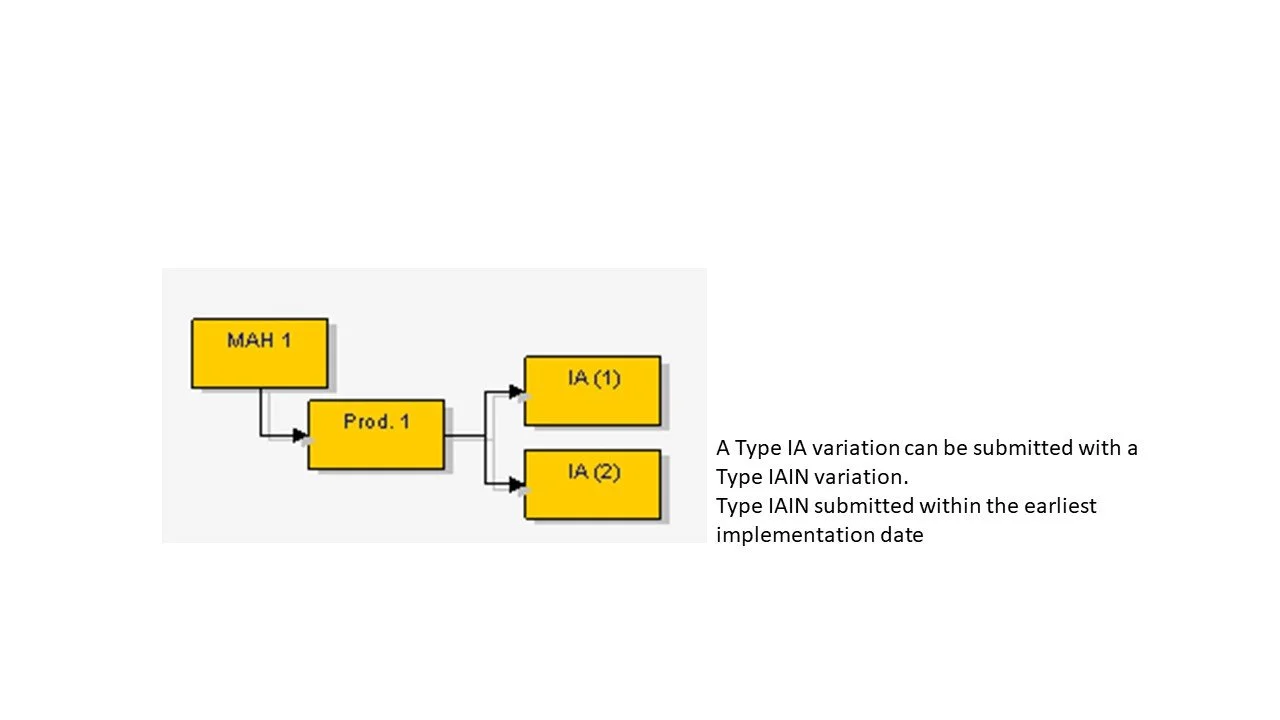

Several Type IA or IAIN affecting one medicinal product (MA) - they are all Type IA or IAIN.

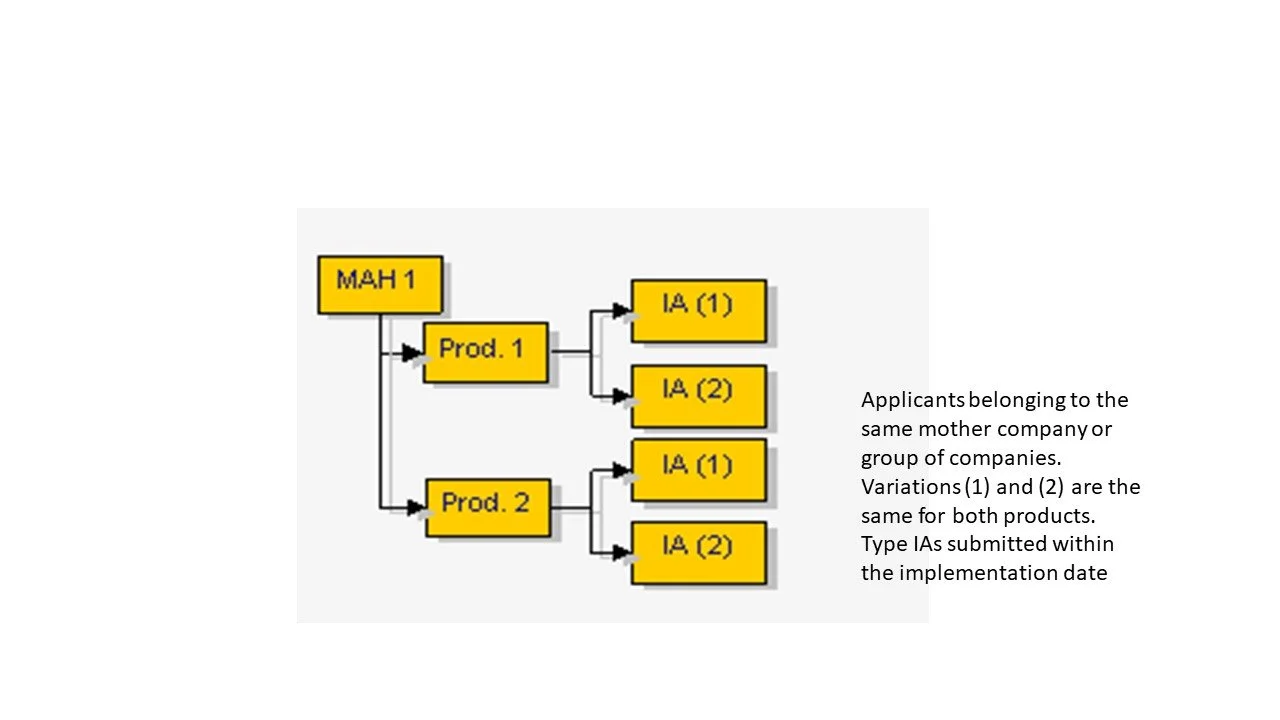

Several Type IA or IAIN affecting more than one medicinal product - the changes must be identical for each medicinal product (MA) to the same relevant authority.

Several Type IA and/or IAIN affecting several medicinal products (MAs) from the same MAH

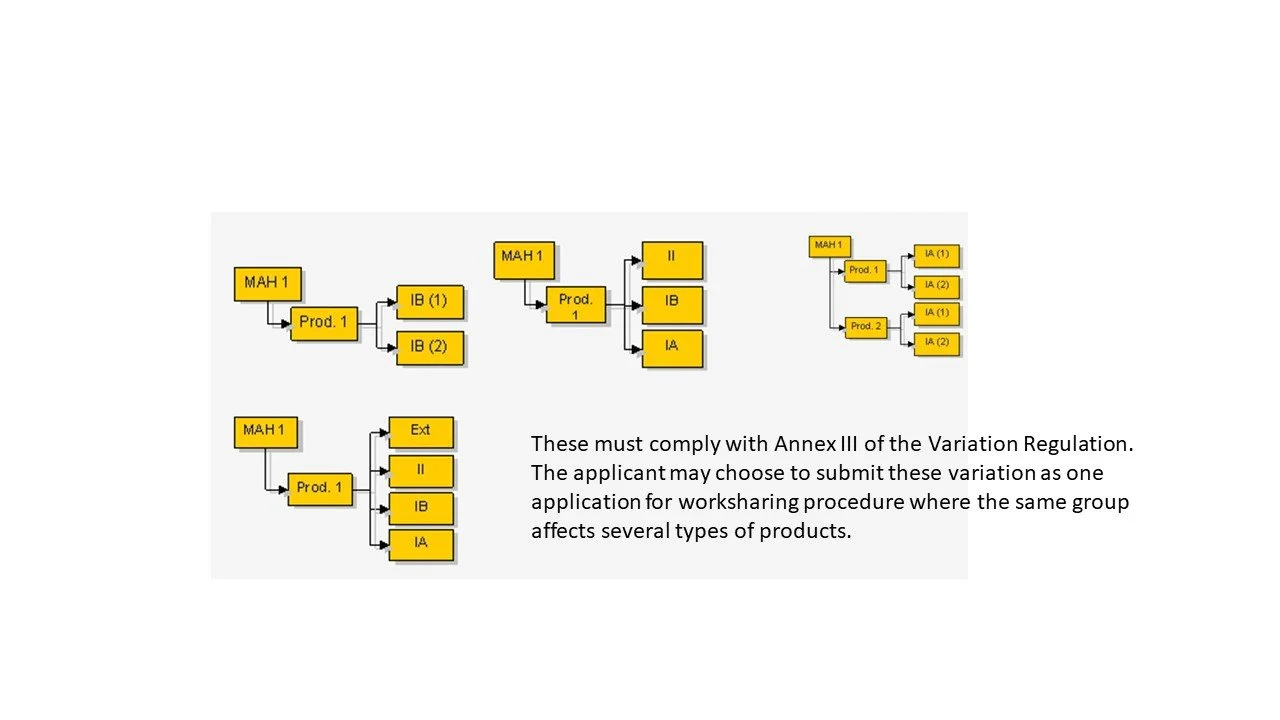

Several types of variations affecting one or more medicinal product (MA) under a single application

Unforeseen variations

Article 5 of Directive (EC) No 2001/83/EC relates to unforeseen variations that are not listed in Annex 1 of the variation guidelines; the MAH can request a recommendation on the classification of the unforeseen variation from the relevant regulatory authority and the regulatory authority must respond within 45 days. In the first instance, check the Article 5 unforeseen variation categories listed on the CMDh website before consulting the regulatory authority.

Behind the scenes – other stakeholders

In my experience, the regulatory affairs department become aware of the requirement for a CMC variation when a change control is raised and the change control document is circulated for discussion by the change control committee during a change control meeting; the change control process is a requirement of Good Manufacturing Practice and is described in the company’s pharmaceutical quality system (PQS).

One that I have done many times before is a batch size increase. There are costs associated with the planning, development and implementation of this change and these are usually discussed and agreed before the change is approved to go to a change control committee. Alternatively, in some companies these points are discussed at the change control meeting.

Some examples of the costs to consider include:

site expansion and additional more advanced, updated equipment

drug product and raw materials to facilitate the batch size increase (audit of sites/contractual agreements)

specialists cleaning materials

environmental considerations such as cost of disposal of materials/equipment

additional site personnel (including training requirements)

Increasing batch size, usually but not always means changes in your manufacturing process and definitely a change in the batch formula. The risk associated with a ten-fold increase is less than that of a greater order of magnitude. There are greater risks associated with a ten-fold increase for certain formulations - such as modified release oral medicinal products and parenteral medicinal products. Stability studies are always initiated at the increased scale.

All of the above is managed by the pharmaceutical company’s quality, manufacturing / production departments as well as regulatory affairs; the change management occurs before, during and after the approval and implementation of the change. The cost of such changes are recuperated by the benefits that the change will bring to patients and the business.

Other regions affected by a variation in the EU

Using the batch size increase as an example, although the variation may be required due to an increase in demand of the medicinal product in the EU market, many pharmaceutical companies supply to other regions in the world, where there are different regulatory requirements.

In fact, some medicinal products are not solely manufactured in the EU and are manufactured in third countries for release to the EU market.

I’ve been involved in variation applications for MAs of a third country linked to the EU MA; sometimes it can be quite straightforward; however, other non-EU countries may require a different submission packages with more or less data and therefore not quite straightforward.

A variation in the EU to add a manufacture site is equivalent to a new MAA application in other countries.

Also, other countries have different procedural timetables and processes that would preclude the use of the new ‘manufactured process batches’ until the approval of the change has occurred in those countries; it has been known to cause delays.

So even though a variation could be approved and implemented in the EU, if the medicinal product which is supplied to other countries, the shelf-life of the medicinal product would need to be taken into consideration; the product would need to be stable enough to withstand the potential delay in regard to the implementation of the change in those countries; I have been in situations where the current stock of batches in those countries needed to be written off - due to timings with approvals and implementation. The local country contacts and the departments responsible for the logistics and supply of medicinal products need to be included in any discussions relating to changes in variation that could impact on the part of the business that they oversee.

The ICH guideline Q12, Technical and regulatory considerations for pharmaceutical product lifecycle management, is an approach that could manage potential Chemistry Manufacturing and Control (CMC) medicinal drug product changes through a Post Approval Change Management Protocol and the other tools described in the guideline; this ensures at least from a regulatory perspectives, that the relevant regulatory authorities can facilitate CMC changes making the whole process for authority approval a little more easier. It should be noted however, that this guideline is pending implementation in many regions.

Some thoughts on variation guidelines

In the guidelines, category and type of variations are based on the potential risk to patients; in other words, the EU adopt a risk based approach for changes to the terms of a MA.

For example, the variation to tighten a specification limit, requires no approval before implementation by a regulatory authority since clearly no detrimental impact on quality is likely to be observed by such a change (at least compared to current authorised conditions); the variation can therefore be implemented through the company’s pharmaceutical quality system and the regulatory documentation submitted either at the next opportune submission date or as part of the annual update.

Hypothetically, a variation to remove a certain population from the special and warnings and precautions section of the SmPC, if the applicant considers it is no longer applicable solely to that population, does require the regulatory authorities to be notified because the risks associated with this change can potentially be significant to the patient. Therefore the regulatory authority would be required to evaluate the data to justify this change. A variation of this nature should of course be approached with due caution; discussion with the relevant regulatory authority is a pre-requisite before submitting that type of safety variation. Hypothetically, if it were approved, one of the conditions would be an expectation for additional monitoring. If the data justifies the applicant’s proposal then the change should ultimately be to provide benefit to patients compared to medicinal products that are already marketed.

I think that it’s good to remember, if you are ever consulted, to assess any proposed variation by applying the principles of risk assessment. Start by identifying the level of risk to quality, safety and efficacy of the product and impact on patient; anything that could potentially impact on the QS&E will require review and evaluation; anything that represents an improvement, generally requires notification. The level of regulatory authority review will always be commensurate with the potential risk associated with the change.

Overall, I would say that the Annex I of the variation guidelines, listing all the foreseen variations is ordered and structured in an intuitive way.

A point to note about variations; updates because of non-technical typographical errors is never really submitted as a discrete variation, unless the errors can potentially impact on patient safety e.g., incorrect dosing information on the SmPC and PIL, due to decimal point being in the wrong place! Regulators expect typographical errors to be corrected at the next planned and applicable variation submission – they should be identified in the application as typographical errors. Also, errors that do not affect the SmPC should be submitted as Article 61(3) notifications.

Another point to note, I’ve sometimes done information updates; these are not strictly speaking variations per se and they are usually because the NCA doesn’t have the latest information because of some unidentified error.

Ongoing studies to further understand, the manufacture, testing and development of the medicinal drug product after obtaining the MA is actually a legal requirement that must be complied with. The MAH is expected to keep up to date with advances in technology that will result in these improvements and implement them by way of a variation.

Things do not always go according to plan…

For variation submissions the first thing to check is the category and the type of variation. In my experience it is really important to get this right. The worse thing that could happen is to submit a variation and to get it invalidated because you have selected the wrong category and code. It is also really important to get the correct ‘Type’ of variation and it is not always immediately obvious. If possible, always consult the relevant authority, in my experience, they are usually very helpful.

Real life though, is not the same as theory; there are often nuances with variations proposed by MAH and these should also be clarified with the relevant authorities. Article 5 relates to unforeseen variations and as discussed above the relevant regulatory authorities should be consulted before submission. The CMDh website lists the categories and types of unforeseen variations; this spreadsheet is continually being updated based upon new information and should also be a point of reference.

For example, when you do select the correct variation category, you might not have the required documentation or meet the required conditions; in such cases if the variation is a Type IA - then it would defaults to Type IB and in the past I have listed this as unforeseen variation with that specific category. If it is a Type IB and not a major Type II, I would obtain advice from the relevant authority as advised by the CMDh website and follow their recommendation.

Attention to detail is very important in regulatory affairs, I would also hasten to add that attention to the right detail is very important in regulatory affairs; invariably there are going to be errors in regulatory submissions; in my experience and when you read the variation guidelines and when working with many national competent authorities, I have found national competent authorities to be pragmatic with regards to missing documents; they do not necessarily invalidate variations ( Type IA/IAIN) due to missing information that can be provided immediately upon request. Bear in mind that this isn’t the position or approach that the applicant should routinely take when preparing and submitting regulatory applications, but I think that regulatory agencies understand that we are all human beings, and their responsibility is not to be an administrative burden but to support industry to provide healthcare to patients in their regions in a timely manner.

Many larger pharmaceutical companies have robust validated systems and computational software for ensuring that the company complies with GMP and their MAs; gone are the days of paper trails and documentation that have faded with time and the information contained therein lost forever. However, situations that can potentially cause problems are company mergers or takeovers. Different operating systems from the companies involved in the merger, may not always be compatible with one another, and the resulting collision leading to instances where the ‘new’ pharmaceutical company is out of compliance with the registered licence details of one or more medical product(s). Mergers or takeovers usually occurs with changes in regulatory/quality staff personnel that can add to or be the cause of the problem. With all the best will in the world, changes may have occurred that were either not captured, fully assessed, or notified to the authorities resulting in non-compliance. Often consultants are brought in specifically to ‘clean up’ and sort things out. A full compliance exercise is usually conducted in such situations; very often variations are submitted as a result of these compliance exercises and an explanation given to the regulatory authorities. I am sure that regulatory authorities are aware of this because they must have encountered variations of this nature on numerous occasions.

Then there are batches that are manufactured where unplanned deviations have occurred; the manufacture of a batch of medicinal product is an expensive process; that is why it is important to have good systems in place to prevent potential batch failures. However, life being what it is, things do go wrong; it’s good to note that within the pharmaceutical industry we learn from our mistakes. We document everything, we investigate, circulate the results and we implement corrective actions. However, for all kinds of reasons an unplanned deviation can occur during a manufacturing run; re-working is not really an option these days; in addition the batch may still be of acceptable quality, safe to use and should be released to the market. I have only dealt with this on two occasions; first in the UK where I submitted batch specific variations, the second was a DC procedure for which the batch was not accepted (mainly if I recall because there wasn’t a process to accept it); in the second case because the batch was still of an acceptable quality it was donated to a developing country. In the UK scenario, the QP had to sign an expert report /quality overall summary addendum describing the specifics of that batch and why, in his/her view, there is no impact on the QSE of the batch. Unplanned manufacturing deviations can result in batch failure, the loss of materials, and financial loss.

However, when things do not go according to plan, a risk assessment is a good starting point because it allows for new information to be assessed and any corrective actions to be implemented. Most importantly, transparency of any errors, mistakes and deviations promote trust between the pharmaceutical industry and the regulatory authorities.

Article 31 pharmacovigilance referrals

Some variations, particularly safety ones are not always initiated by the MAH. An ‘Article 31 pharmacovigilance referral’ follows the provisions of Article 31 of Directive 2001/83/EC. The procedure is initiated as a result of the evaluation of data relating to pharmacovigilance of an authorised medicinal product(s) by the Pharmacovigilance risk assessment committee (PRAC) and it involves certain MAs. The PRAC is a committee within the European Medicines Agency responsible for the assessing and monitoring human medicines.

Whenever an Article 31 referral was initiated, I noted that there is a certain buzz of excitement and expectation in the regulatory affairs department. It’s because usually, the affected MAs require a timely Type IAIN submission; for a generic company, the likelihood is that a lot of licences are affected by the request and the changes should be implemented in the next manufacture run. The buzz and excitement is caused by the pressure around co-ordinating with the manufacturing facilities and local country contacts and the relevant authorities to submit and implement the change on time.

Completing an Article 31 referral application is a good experience for a regulatory professional and you can learn a lot from the process. One Article 31 referral that I was involved in did not just affect the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC), Labelling and Patient Information Leaflet (PIL). I recall an update to the risk management plan and the need for a communication to the Healthcare Professionals was identified and progressed at the time. The good news about Article 31 referrals is that the guidelines have a specific category for this referral, and the Agency provides the text for the SmPC, Labelling and PIL, therefore in reality, it is more of an administrative activity.

Article 29 referrals

For Type II variations and worksharing variations for MR and DC procedures, concerned member states have the option to disagree with the decisions for approval of a variation by the reference member state. However, the reason must be because the concerned member state(s) identifies a potential serious risk to human health that prevents them from recognising the decision of the reference member state. The reference member state will then refer the application to the corresponding coordination group for a separate procedure (Article 29 referral) to evaluate and reach an opinion on the concerned variation(s). More information can be found on the EMA website. I must add that I haven’t been involved in an Article 29 referral for variation applications only for MAAs. Let me know if you have experience in a Article 29 referral for a variation application.

Some thoughts on pharmaceutical companies’ goals

Pharmaceutical companies respond to the financial benefits of marketing medicinal products in certain countries. Sometimes the company’s goal is to have a footprint in a particular country or region; some pharmaceutical companies operate in a niche market environment. Politics can also play a part in the pharmaceutical industry, as seen with regards to the demand for the supply of Covid-19 vaccines during the last (current!) pandemic. Other times, the consideration is more of an ethical one, such as supply of medicines to developing countries.

The regulatory professional plays an important part to fulfil a pharmaceutical company’s business goals and mission. Post authorisation regulatory activities also support in achieving the pharmaceutical company’s goals.

Finally…

Hope the blog was useful - please give feedback and any subjects that you specifically want me to discuss